Bumper weeknotes this week, as I’ve had lots of time on trains for writing (and some sightseeing too).

- Reflections on Inclusive Information Infrastructure from work with LandPortal.org

- Nourishing insight: timely, not fast

- Civic technologies and the pathways to government responsiveness

- Avoiding unpaid (and unjust) labours of governance

- Other reading this week

Reflections on inclusive insight infrastructures

At Connected by Data, we’ve recently started a project with the Joseph Rowntree Foundation (JRF) to carry out ‘ecosystem mapping and engagement’ to support the development of an ‘insight infrastructure’ on poverty in the UK. Put broadly, JRF, as a widely respected research, policy, advocacy and delivery organisation, are looking to explore how they can take an infrastructure approach to support and enable faster, deeper and more relevant insights into both the problems of poverty, and their potential solutions.

In particular, the work is motivated by a sense of ‘missing data’, including in terms of data’s timeliness and representativeness. That is, the insights or analysis that might be needed to direct policy or programming often comes too late: seeing problems in the rear-view mirror, rather than as they emerge, and data sources often excluded information that reveals the communities most affected by particular issues, or that don’t provide insight into the lived experience of those affected individuals and communities.

As part of the work we’ll be talking both to people from organisations who are users or providers of poverty-related data in the UK (look out for the survey we’ll be sharing next week), and to those who have worked on other forms of ‘inclusive insight infrastructure’.

One such organisation is The Land Portal, and, as chance would have it I’ve been with the Land Portal team in Rome this week to run a strategy refresh session at the Land Portal team and board retreat. In preparation, I took a look back at ten years of Land Portal strategy evolution. Over that time the organisation has iterated through a range of approaches to creating “An open, inclusive, and democratic land information ecosystem that helps decision making, policy, and practice at all levels” [1].

Strategy Cycles - Iterating an Infrastructure

Starting out as a Drupal-based website, aggregating news, publications, discussions, and selected datasets on land governance, and primarily organising these by country, the first strategy refresh for Land Portal in 2013 focussed on two themes: modularisation and localisation. Turning the different features of the site into clear components (Library of Resources, Country Profiles, Debates) was intended both to support easier technical management, and to help users more clearly locate the kinds of insights they were looking for. The localisation strand explored how to give partners, particularly those in the Global South, greater ‘ownership’ of the portal, proposing the idea that partners might ‘adopt’ country or regional pages of the site, and take responsibility for curation of content and data in those areas.

The idea was that in working with partner organisations who operate closer to the grassroots in particular countries, knowledge, data and insights that rarely feature in ‘global’ publications could be better identified, shared and promoted. In practice, this aspect of the strategy had mixed success: grappling with the challenge of the value proposition for local partners, who don’t always directly benefit from putting their content and insight into a shared infrastructure, which can end up feeling extractive, even when seeking to provide a platform and service that is aligned with the goals and values of the local partners.

The 2017 - 2021 Strategy maintained the goal of diversifying the land governance information ecosystem, but took a different tack, placing the focus on capacity building, standardisation and a land portal service offering. It recognised that while the idea might be to equip knowledge producers large and small to adopt open standards when they publish data and insights, in practice, many lack the ability to do so, and so Land Portal may need to provide technical workflows that help to extract information from where it is published, and enrich it to make it more accessible to portal users. This strategy cycle explored how to open up APIs onto Land Portal’s core data services, to encourage others to integrate Land Portal-facilitated data into other information services and offerings. And it explored how to be more responsive to user requests, both through creating spaces for feedback, or participatory governance of resources like LandVoc, and by offering elements of Land Portal, such as debate hosting, or social-reporting on events, as a service.

This last element came into its own during the COVID pandemic, when Land Portal was able to support a range of organisations in moving their events online, using Webinars and online discussions in place of conferences. Land Portal’s wide-reaching mailing lists and communication channels have proven particularly effective at creating online discussions with regionally and sectorally diverse participants and audiences. However, a focus on service provision has also created a risk that the thematic focus of the organisation is shaped by outside commissioners with the budget to buy-in support, rather than by the priorities Land Portal team identify from the field.

In 2021, the Strategy adopted a framework of ‘Open, Informed, Debate’, reflecting for the first time the growing work of the Land Portal to advocate for open land data from governments, primarily through the ‘State of Open Land Information (SOLI)’ reports, which provide an assessment of data availability in order to support collaborative efforts to make data more accessible. Through a process over the last year to refine the Land Portal’s Monitoring, Evaluation and Learning framework, an updated Theory of Change has been published that highlights how different stakeholders consume and produce insights through Land Portal.

It is worth noting that there have also been a number of key developments over the Land Portal’s history that fall outside of the strategies above. For example, learning from the early localisation experiments, the Land Portal now has a local researcher network of regionally based directly commissioned researchers (Local Knowledge Engagement Network) who produce country and thematic profiles, and identify potential new data and information sources. Data stories have developed as a key information product, both using data to communicate particular insights, and exploring issues in the quality and availability of data. And collaborations with the Open Data Charter and Global Data Barometer have added to the toolbox Land Portal has available to support country adoption of more open land data policies and practices.

Strategies summarised

From all the strategy cycles above, we can distil a number of interventions that have been tried and that remain part of the Land Portal’s insight infrastructure:

-

Aggregation - the platform aggregates and indexes data and documents, making it searchable, categorising it using an openly developed taxonomy (LandVoc), and standardising data to make it available through common visualisation widgets.

-

Capacity building - to support marginalised actors to have their insights indexed.

-

Commissioning - particularly country and thematic profiles that are presented with a combination of editorialised narrative, live data, and related content.

-

Curating conversation through Webinars and debates with a diversity of voices, in order to surface tacit as well as official knowledge and insight.

-

Monitoring - the availability of key datasets in particular countries, and highlighting gaps in data availability.

-

Advocacy - to encourage powerful information actors to open up their resources for wider use.

Lessons for a UK poverty insight infrastructure?

The interaction between ‘infrastructure’ and ‘ecosystem’ is a complex one. This recent piece from Maria on Crooked Timber offers a rich theoretical look at what makes a functioning ecosystem, with different entities interacting through ‘competition’, ‘predation’ and ‘cooperation’, and quotes Robin Berjon’s statement that “in an ecosystem everything is infrastructure for everything else.”. Land Portal has seen this play out a number of times. Understanding that the local actors who might contribute to, or use insights from, a shared infrastructure are also involved in a web of relationships of competition for funding, collaboration to deliver services, and mutual interdependence, can be useful for thinking about how more national or global information resource either is perceived, or how it ultimately affects them.

For Land Portal, building a role as a trusted broker, seeking to balance an unbalanced information environment, and ‘share the mic’ through amplifying diverse discussions has been key. This makes me think we may want to explore questions of trust in our upcoming ecosystem interviews. What would make the insight infrastructure JRF are developing feel like something to trust in? Would it make a difference to users if they could see that a diverse group of individuals were involved in governance of the project or platform?

Land Portal’s experience also points to a useful connection of activities that I’ll describe as: curate, commission, capacity build, campaign. That is: curate the data that is available by providing accessible and contextual meta-data; commission summary content that extracts key information from the data and provides ready to use stats and synthesis; capacity-build with local organisations to both help them access and use local data, and to publish data and information from their perspectives; campaign for better data from powerful actors. I’m not suggesting this model either represents fully what Land Portal does, not that it’s directly transferable to JRFs project, but it does help me reflect on one way to fit together different infrastructural activities.

And, of course, Land Portal is just one example of an ‘insight infrastructure’. I’m keen to talk to folk involved in others, so if you’ve got an idea for someone I should talk to (or if it is you) please do drop me a line.

Timely not fast

In preparation for a roundtable next week, I’ve been reading Shushana Zuboff’s latest paper on ‘Surveillance Capitalism or Democracy’, which outlines how ‘meaning blind’ networks, driven by engagement metric feedback loops, can create a diet of information void of truthful or informative content.

This got me reflecting on the traps that an ‘insight infrastructure’ of the form we’re helping Joseph Rowntree Foundation to scope out could fall into of prioritising ‘fast’ over ‘deep’ insight.

I was also thinking of this as I took a four day train trip to Rome and back. The travel is relaxing and slow, but often the changes between trains have left little time to find a lunch or dinner for the day. I made the mistake at the start of grabbing the ‘fast food’ options: instantly filling and satisfying at first - but not the long-term nutritional answer. Instead, what I need is a timely diet: places with food that’s ready to go, but that might have taken a little longer to prepare. It takes a bit more seeking out, is less familiar, and often takes a bit longer to digest - but it’s the right option.

So - when we think about timely insight, we need to be careful not to immediately assume that it means ‘rapid’ or ‘real-time’, but rather to think about the actions that insight needs to be in time for, and the other qualities that make an insight timely.

Civic technologies and the pathways to government responsiveness

I finally caught up with reading a new paper from Jonathan Mellon, Tiago C. Peixoto and Fredrik M. Sjoberg which examines the demographics divide in terms of who participates through civic technologies, and questions whether this results in a difference in who benefits from that engagement.

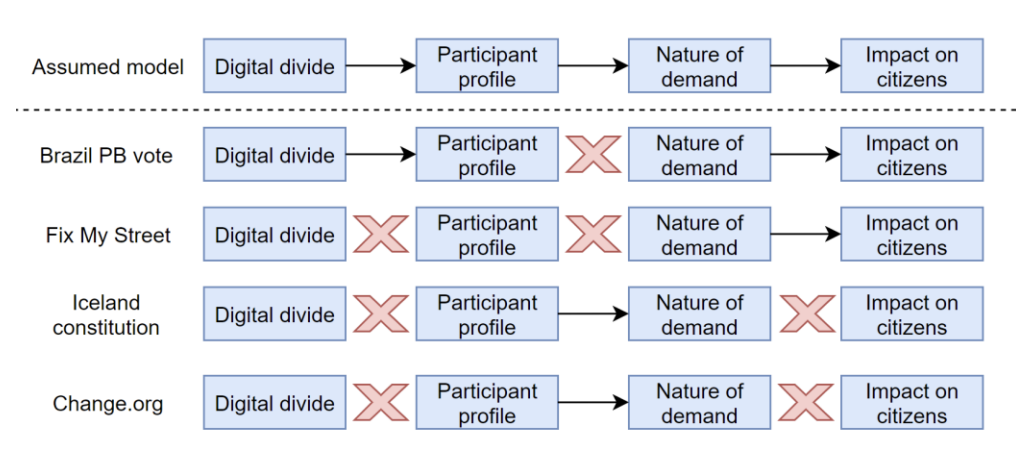

They outline an ‘assumed model’ of transmission between participation and impact, in which demographic digital divides (e.g. more men than women online; or more urban users on a particular platform used for engagement) may translate into biases in the profile of those who participate in a civic engagement opportunity. On the assumed model, this then leads to a consequent bias in the demands made through the platform, and ultimately leaves the interests of those citizens with connectivity and ability to speak up through civic tech with better outcomes. In short, the assumed model says that biassed access leads to biassed participation leads to biassed outcomes.

Using four case studies, they suggest that the picture is actually more complex than this. In each case they look at, at least one of these ‘transmission mechanisms’, from digital divide to unequal outcomes, does not operate as the assumed model expects. Either the nature of demands made does not appear to disproportionately serve only those who participate, or decision makers do not simply respond to demands based on e-participation input, but may factor in a much wider range of influences when allocating resources or making decisions in response to a participatory process.

The authors sum up their work with this:

“Is digital civic engagement good or bad for democracy in terms of aligning policy with the preferences of the population? …our results suggest that the demographic composition of participants is only part of the answer to this question. Just as important to policy outcomes is how the platform translates civic participation into policy demands and how government responds to those demands.”

We can read across from this to the design of participatory data governance activities. In some cases, seeking a ‘representative sample’ of the population is important, but on it’s own, it is not enough to create policy aligned with public interest. The process needs to also translate diverse representation into demands that can impact policy making.

Avoiding unpaid (and unjust) labours of governance

Abeba Birhane and Deborah Raji pick up on the recent attention given to Large Language Models, such as OpenAI’s ChatGPT, and ask why the well-grounded critique of the harms they cause is not sinking in. They highlight the unpaid labour that marginalised groups are asked to do right now to make such systems ‘better’:

“Although the choices of those with privilege have created these systems, for some reason it seems to be the job of the marginalized to “fix” them. In response to ChatGPT’s racist and misogynist output, OpenAI CEO Sam Altman appealed to the community of users to help improve the model. Such crowdsourced audits, especially when solicited, are not new modes of accountability—engaging in such feedback constitutes labor, albeit uncompensated labor.”

I’ve dropped a placeholder into the briefing on participatory data governance I’m working on to make sure we try and address this theme of unpaid governance labour, as well as always remembering that an option on the table in any data governance process should be to ‘just stop it’.

Other reading this week

-

The ‘Paradox of Open’ response essays including Jeni’s response on ‘Creative Communities’

-

Mastodon Isn’t Just A Replacement For Twitter by Nathan Schneider and Amy Hasinoff, looking at the concept of subsidiarity in platform governance, and sharing lessons from social.coop’s exploration of participatory content moderation and platform management.