I actually wrote most of this post almost a year ago, after a trip up to Aberdeen for the Royal Statistical Society Conference 2022, where I was invited to speak for the Significance Lecture. It’s one of those pieces of writing that I didn’t quite finish and therefore didn’t post.

One of the questions I received after my talk (well, it was more like a five minute critique but I’ve moved on) came from a professor with a focus on medical and research ethics. One point she made, as I understood it, was that our personal ethics matters when talking about what we should and shouldn’t do with data, so we should describe our personal ethics when talking about anything to do with ethics or responsibility more generally.

This made me think about my own ethical framework – how do I think about how to determine what’s good or bad – as well as the effectiveness of individuals to shape data ecosystems and the relationship of ethics to the kind of collective and participatory data governance we’re focused on.

It’s coming to the fore for me again now because of what some people characterise as the AI Safety vs AI ethics division. The “AI Safety” movement has gained sufficient force in the UK that the Summit here in early November is called the AI Safety Summit (though I have to say it’s not clear to me how much the UK Government understands the distinctions between these different ways of thinking about responsible AI development).

“AI Safety” is associated with what Timnit Gebru and Émile Torres have described as the TESCREAL set of beliefs. (It is worth reading both Torres’ recent piece and this critique of the TESCREAL analysis.) It focuses on the existential risks of general purpose AI, rather than the range of other challenges that are well summarised in this week’s report from the UK Parliament’s Science and Technology Committee on AI Governance.

This focus on existential risk is driven by the values held by predominantly rich cis white men, who hold such privilege and power that the only thing they see as a risk is a super-powerful AI. It’s interesting to think about which values such an AI might have – aside from the obvious ‘kill all humans’ impulse – that would be a threat to them.

Care ethics

The AI Safety crowd generally adopts a long-termist utilitarian ethical approach, saying the things that should be done now are those that will benefit most people, including the majority of the human race as a whole, namely our collective descendants in the future. As a consequence, adherents tend to focus on long term threats, including climate change and general AI, over current issues and injustices.

This contrasts with the ethical framework I now favour, which is care ethics. This ethical framework focuses on relationships, compassion, treating each other as individuals, and the context-dependence of what is right or just, as opposed to the equation-based approach of utilitarianism. I believe that if people treated each other with care, the world would be more just, equitable and sustainable, as an emergent property.

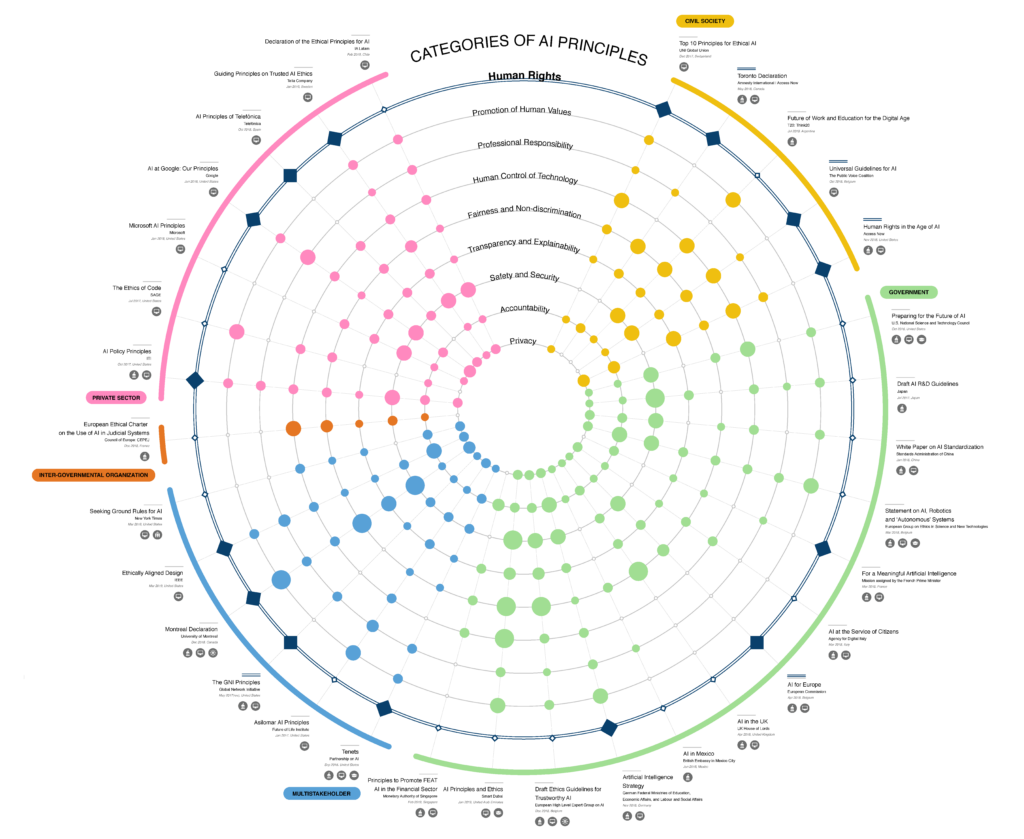

The field of “doing the right thing with data and AI” has been focused on ethics for a while now. Large numbers of broadly similar ethics principles have been produced, nicely summarised in this diagram from Principled Artificial Intelligence: Mapping Consensus in Ethical and Rights-Based Approaches to Principles for AI from the Berkman Klein Centre in 2020.

Most of these ethics frameworks aim for generalisable standards of behaviour, which the Berkman Klein Centre paper summarises into themes of “privacy, accountability, safety and security, transparency and explainability, fairness and non-discrimination, human control of technology, professional responsibility, and promotion of human values”.

From a care ethics perspective, these might well be good things in many circumstances, but what is more important are the relationships being built, the voices being heard, the compassion being shown. Current data or AI ethics frameworks rarely address these needs, and I think that’s why we’re finding they’re not all that effective at either stopping bad things from happening or giving people agency in the process.

Applied data and AI ethics

The other area where I think the current crop of ethics principles fall down is in how people expect them to be applied.

Ethical codes of practice that focus on individual responsibility work ok for professions such as medicine where you can’t practise without formal recognition, and there’s therefore real motivation for an individual to behave according to those codes. They are not effective for skills like data science or AI development where there aren’t (and I don’t think will or should be) those same pressures.

Ethical principles at an organisational level are similarly flawed, but here because they are frequently too generalised to be easily applied, and management or governance layers rarely examine whether they are or not. For example, it’s easy for a set of ethical principles to include the word “Transparency” but in practice there are degrees and levels of transparency, and limits due to commercial sensitivities, privacy protections, or interplays with other principles such as security. Worse, principles that fall under the general theme of “promotion of human values” provoke questions about whose values take priority, for example in the tension between freedom of expression and protection from discrimination and hate speech.

In other words, I don’t think people or organisations will do “good things” with data or AI just because they develop and subscribe to a set of ethical principles. Real-world granular decisions are too context-dependent and nuanced, and the people who make them are too constrained by the wider systems in which they operate.

Care ethics in data governance

These challenges with applying ethics principles is why I’m much more interested in data governance than data ethics. To me, data governance is about shaping systems and processes that nudge or constrain organisations to do “good things”. Effective data governance is more robust and trustworthy than depending on the individual ethics of data scientists or digital teams (though makes it harder to get individual accountability when it goes wrong). Data governance is more able than data ethics to respond to context and special circumstances, and thus demonstrate care. It is more able to respond to changes in norms and values over time.

The kind of collective, democratic, participatory, deliberative and powerful data governance that I and we are advocating for reflects my personal ethics of care in the way it emphasises relationships, inclusion and voice. It can be used to create (and I think is essential to) a just, equitable and sustainable world.

This approach to data governance also by definition allows for different communities to recognise the inherent trade-offs and nuances in terms like “justice”, “equity” and “sustainability”. It allows some communities to aim for other goals when they adopt data and AI, such as “liberty”, “purity” and “authority”. It also allows communities to adopt different ethical frameworks for thinking about what “good” even is.

Care ethics in AI development

I think care ethics could also be applied in AI development more widely than in data governance.

I had a chat recently with Which? about their work on sharing data to prevent fraud. Fraud, especially identity theft, can be devastating for people as well as losing money for businesses and governments. Applying care ethics, we would focus not only on the experience of victims but also on that of people unjustly accused of fraud (such as those embroiled in the British Post Office scandal) and even on fraudsters themselves, some of whom may have committed fraud through ignorance, error or desperation. We would focus on how data sharing and automated decision making would affect not only them but their relationships with other people, such as their families, friends, or colleagues, and organisations such as their employer or the government.

Applying care ethics requires us to consider the effects of the whole system into which automated decision making is introduced. It naturally leads to designing systems that assume the best of people, recognise that both humans and computers can get things wrong, and that provide easy and compassionate routes for challenge, correction and redress when that happens.

I hear a lot of people talking about being human-centred with data and AI. I think being care-centred is more important.