AI Adoption

I posted recently about the challenge of adoption of AI by the public sector.

There are two sides to this: how the public sector adopts AI itself, and how the public adopts AI-driven public services.

I used to think that any shortfall in adoption of digital services was something that would just fix itself over time: that with greater connectivity, more access to cheaper devices and a greater proportion of people becoming digitally literate, more people would use them.

This post from a member of our People’s Panel on AI is one of the things that made me reconsider.

I talk to many older people whilst working in a busy cafe, and I hear what they are saying … It’s now so difficult to access over the counter assistance with personal finances, the paying or querying of utility bills, the making of a simple doctor’s appointment, or the reissue of a prescription … as we are faced with the closure of local banks, post offices, even the smaller shops, and encouraged to conduct all our affairs on-line … a remote world minus all personal contact and friendly interaction … these changes to procedures are felt the most acutely by the elderly … we have taken away from them the element of choice, for them face-to-face contact will always be important.

There will always be new tech that older people struggle with. I’m fairly sure I won’t enjoy direct brain interfaces, even if my (future) grandkids do.

But also, some people won’t use digital public services because they find value in things other than efficiency. Most importantly, humanity: receiving care and being seen as a whole person.

Faceless bureaucracy is dehumanising; digitally intermediated and automated bureaucracy doubly so.

Similarly, on the public sector worker side, tasks characterised as drudgery that should be automated might have broader importance and benefit to some workers.

The act of reading consultation responses doesn’t just produce a summary or sentiment measure, but is a way of learning more about the topic and ecosystem. Writing notes can help ensure your mind doesn’t wander when listening to someone. Writing reports (done well) stimulates reflection and learning. Mindless tasks refresh you for mindful ones.

When considering what to automate, we shouldn’t just consider the outputs but the deeper outcomes of these tasks.

(And we should definitely avoid the ridiculous situation where we use AI to summarise AI-generated responses to bids, consultations and applications. AI outputs being fed to AI inputs means it’s time to use a different approach altogether.)

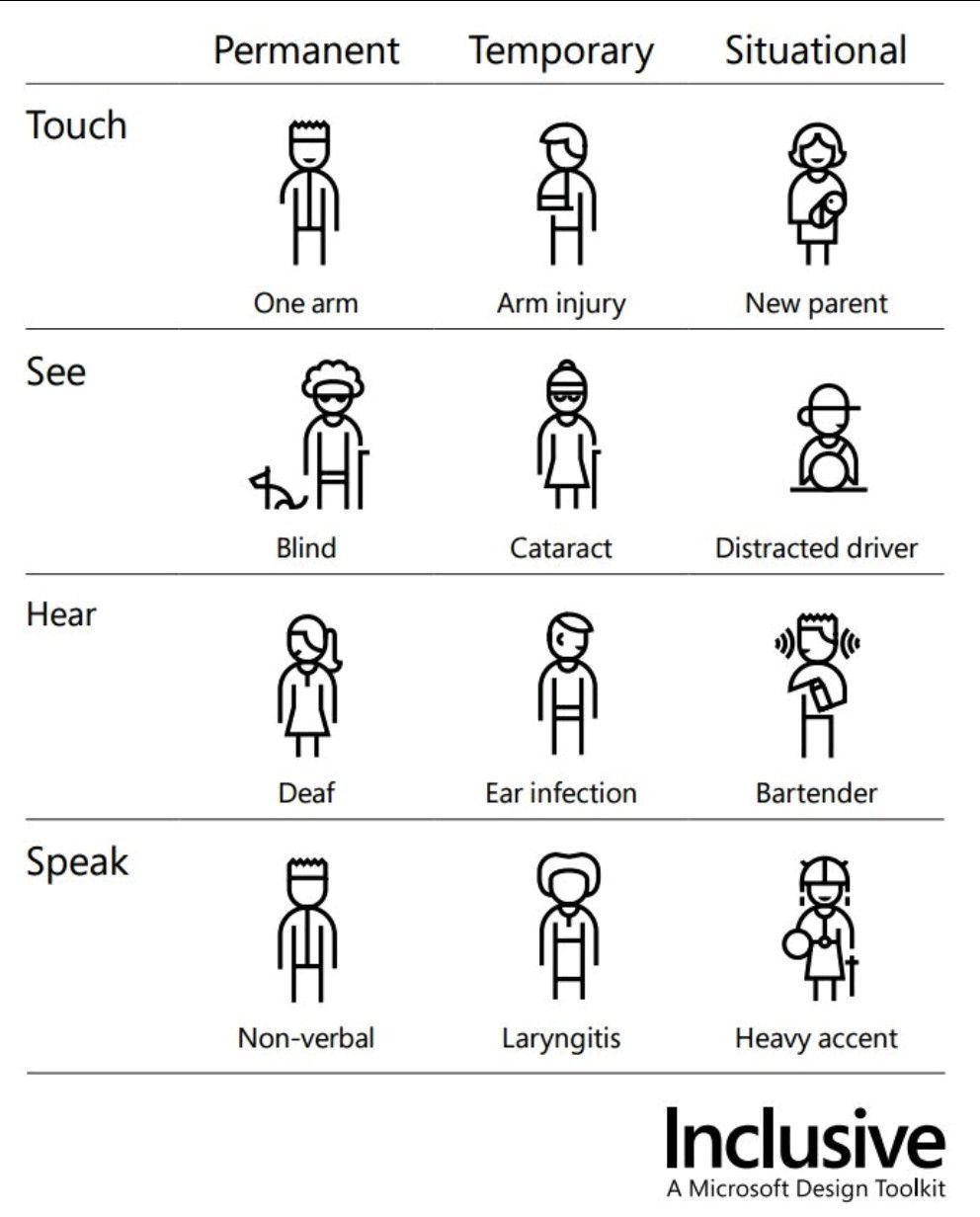

We can also borrow from thinking about accessibility: some people might never use digital services, some be temporarily unable to (perhaps they ran out of data or their mobile broke) and some just not want to because of their situation (eg if it’s delicate, complex or stressful).

So when looking at adoption, I think instead of digital exclusion we should be talking about digital diversity.

Exclusion implies there are barriers that can be lifted.

Diversity recognises we need a range of different things from work and public services, at different times

Some people will be super happy with their own personal AI assistant, at least most of the time. They might even find it better than dealing with a human for some things. But other people will want to be able to talk to someone real, even if only occasionally.

The same considerations apply to public sector workers. Some may love not having to ever interact with citizens, or be delighted to focus on quality control of AI decisions. For others, human contact might be the most fulfilling part of their job: what satisfies and retains them.

System impacts matter too. When people need help but can only interface with govt online, they turn to others for support: to carers, GP receptionists, librarians, Citizen’s Advice etc.

The human work doesn’t go away, it gets distributed elsewhere and becomes invisible.

Yep, this is my parents, in their 80s, trying hard to use it but baffled by apps, alerts, text messages with codes they have to input. They can't easily get through on the phone, so have started just going the surgery and standing at reception when they need to speak to someone.

— Rose Nightingale (@RoseNightingal1) June 24, 2024

Similarly, when workers don’t get on with the technology they’re told to use, they work around it, ‘wasting’ time and creating risks.

Both the public seeking help and public sector workers using workarounds are signals, not errors to be suppressed. They highlight areas where systems can be improved. They also highlight the diversity of user needs.

We need learning processes to pick up on these signals.

I'd also draw on @snowded's "Managing complexity (and chaos) in times of crisis", which includes a bunch of concrete recommendations based on the Cynefin framework around how to set up these learning structures in complex, changing systems.https://t.co/ICit11Bpg4

— Jeni Tennison @JeniT@mastodon.me.uk (@JeniT) August 16, 2024

So I think the adoption challenge should be reframed in terms of iteratively (a) understanding the contours of digital diversity through user research and co-design and (b) perfecting the accommodation of diverse approaches and easy hand off between different modes of interaction

But, you say, this sounds like more work! What about cost of delivery? What about waiting times and throughput?

And I will point you to examples like court digitisation where failure to work with people was not only costly but increased court delays.

We will have better outcomes if we honour people’s digital and AI preferences in the same way we do diverse accessibility needs. If we listen to what people want and give them autonomy rather than imposing our fantasy AI futures. If we aim for satisfaction rather than adoption.