Tim presented at a meeting of the Local Government Association’s AI Peer Network on “Giving communities a powerful voice in governing AI”, sharing practical approaches to embed participatory practices in decisions about data and AI at a local level. The meeting also included a presentation from Megan Lawless on the Manchester People’s Panel for AI.

Slides and a transcript of Tim’s presentation are shared below.

Access the slides with speaker notes here.

Why engage? The participatory AI imperative

I don’t need to explain to this group what AI is, but I think it’s useful to establish some of what makes public participation around AI different 1.

Ever since the rise of Weberian Bureaucracy in centuries past, governing has been about algorithms: about setting out and following rules designed to deliver services that deliver a degree of procedural justice.

Algorithms are everywhere in the public sector: from school admission codes, to complex rules for prioritising child protection interventions. Some are implemented ‘to the letter’, others, in practice, describe idealised or incomplete processes that in practice leave lots up to discretion. However, with an old fashioned algorithm you can usually trace back to see the rules, and check at each step of the process, whether the rules or procedures have been followed.

However, modern artificial intelligence is different. With AI you can either specify the inputs and apply a model to look for patterns, or specify outcomes and then train a system to make decisions that approximate these: all the while being relatively agnostic about the steps that go on inside the black box to get there.

This can unlock all sorts of new potential, but it also raises a range of challenges.

-

Firstly, the legitimacy of an AI system, and public trust in its outputs, will rest not on being able to point to exactly the rules the system follows - but by pointing to the way a system was developed with involvement of those it affects. After lots of national media coverage of AI risks, both existential and to jobs and employment, public concern about AI is high and growing: and local authority use of AI needs to be approached with transparency, openness and public engagement.

-

Second, AI can produce outcomes in new ways. Simply replicating existing bureaucratic processes ‘but faster’ with machine-learning is a recipe for disaster. Instead, we need to take a step back to the design of services, and check with publics where AI can be used to deliver better outcomes and how it can address, rather than reinforce, hidden biases of our existing processes.

-

Third, an AI system is only as good as the data that goes in. But if the data you feed into a process is not representative of affected communities, a system might have serious unintended consequences.

-

Fourth, AI models themselves, often trained on vast datasets, or with reinforcement learning feedback, embed certain biases - and it’s important to understand with affected communities the trade-offs that are acceptable, and the red lines that should not be crossed.

Affected communities and the governance stack

Now, I’m quite explicitly talking here about the importance of engaging affected communities. That is, effective participation needs to give real voice, and real power, to those most affected by an AI system.

For example, if you are introducing a system focussed on prioritisation of social care resources, then it’s vital that plans to engagement include people in receipt of social care, and potentially some of those who currently miss out, but are seeking support.

With any AI project, it’s important to map out who might be affected, and think about how to engage them.

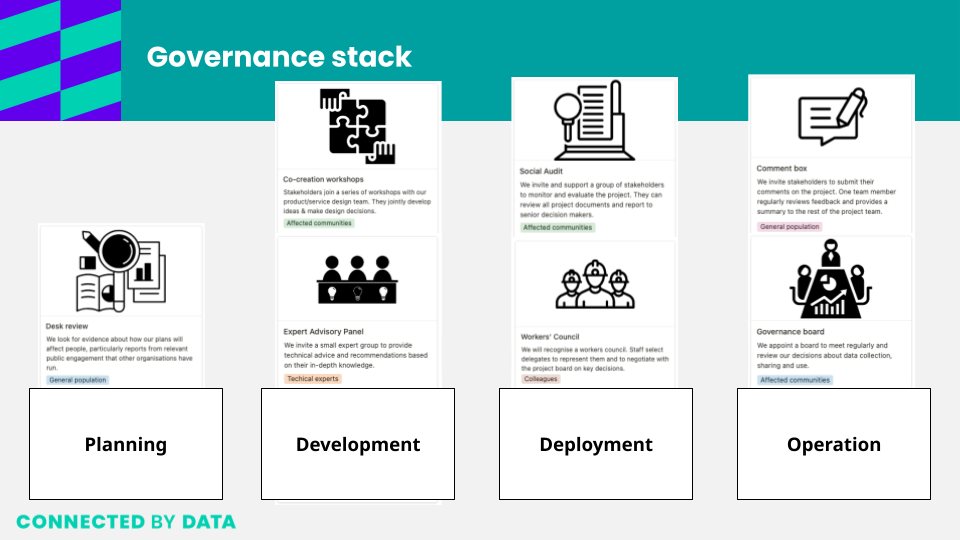

However, powerful public participation doesn’t come from one-off workshops with an affected group. It engages affected communities as part of the wider ‘governance stack’ of the initiative.

After looking at many different case studies of participatory processes around data and AI, we were struck by how success comes not just from choosing accessible and engaging methods to reach publics, but also from linking different forms of engagement, and bringing managers, technical teams and frontline staff on the engagement journey too.

We are in the middle of developing a workshop game to explore this - with the working title ‘Governance Stack’, which invites players to think about the range of stakeholders to involve, and the range of methods to use, across the lifecycle of a project.

For example, on the screen is the outcome of playing a round of the game selecting methods that could be used in developing the social care AI applications I mentioned earlier:

- In the early stage of planning an AI project, you could focus on existing evidence through a desk review on the kinds of opportunities and risks of this AI technology, seeking to understand affected communities;

- When it comes to development, co-creation with a group of affected community members, combined with inviting expert advisors, could inform development;

- At deployment, you might consider ways to engage both frontline staff, and a small number of representatives of local citizens, to oversee roll-out;

- And when it comes to ongoing operation, open feedback channels, and a place for affected community representatives on a governance board, can ensure issues for improvement are identified and addressed early.

Seeing all these different components of engagement laid out can feel a bit overwhelming at first - but they often build on one another quite naturally - and as you develop the culture and the infrastructure for participatory engagement around AI, it can become easier to see how to regularly embed the voice of affected stakeholders.

The other things I want to note before I move on to look in-depth at two practical methods for giving communities voice in AI governance, is how the stack of approaches supports a journey of learning and adaptation, both for the AI project, and for members of affected communities - who might come to explore and learn about an application of AI through co-design workshops, and engaging with an expert panel - but then some of whom might go on to be involved in ongoing governance and oversight processes.

As soon as we release a first playable version of Governance Stack, I’ll share it with the AI Network, so you have a resource for creative discussions over possible participation approaches.

In the meantime, I want to share more on two specific approaches to community engagement we’ve been looking at at Connected by Data: participatory pilots, and citizens reviews.

Participatory Pilots (1 - 2 - 3)

Not all applications of AI will involve building something new, or a full development cycle. In fact, many uses of AI in the public sector could be as simple as turning on a feature in enterprise software, or picking up an off-the-shelf tool to use in an existing activity.

For example, using AI tools to summarise consultation responses, or to draft letters to residents.

The framework of a participatory pilot can be useful to keep in mind for these kinds of small opportunities, and it can be as simple as 1, 2, 3.

1. Evaluate AI capabilities and develop an experiment

The first stage involves verifying assumptions or claims about what AI can do.

For example, if you are considering using AI to summarise lots of information - run some tests to see how it performs?

Is it: Great? Good enough - considering potential time or opportunity cost savings? Or it is inadequate?

There’s no point pursuing tests of tools that are just not there yet. On the other hand, if an AI tool is showing promise, taking a bit of time to get behind the marketing messages to get a feel for its strengths and weaknesses can help you to then plan a suitable experiment.

An experiment should let you gather evidence about how an AI tool will work in practice. You might find you can run a natural experiment - for example, comparing an existing human written report, to one generated from the same evidence by AI. Or you might be able to design an A/B test, where you carry out some tasks with AI, and some with the existing process. Or you might set benchmarks that an AI tool must meet, such as predicting the right case outcome 95% of the time.

2. Identify affected stakeholder & ethical issues

With an experiment identified, you then can then think about who might be affected.

For example, if we are using AI to summarise consultation responses, there are the people submitting those responses, and the staff members wanting to understand them. Or if we are exploring AI use to handle incoming school admission queries, there are parents whose enquiries are being sifted.

We can also think about the particular ethical or practical issues that might come up, which might help identify further affected groups. For example:

- Does the proposed application of AI use data in-line with clear informed consent, or are we seeking to use data in a novel way? Whose data is being used?

- Will it be transparent that AI is in use? Who should it be transparent to?

- Is there risk of biased decisions from this AI tool? Who might be particularly affected by bias?

Depending on the situation, you might have direct access to affected stakeholders, or community representatives, or you might need to reach out to partner organisations who can help you find groups to engage with.

3. Pilot in partnership

Then, with your stakeholders identified, bring them into discussion of your pilot.

This can be as simple as one or two meetings, or as in-depth as the pilot needs.

Explaining your pilot plan, and hearing any questions or concerns from affected stakeholders before you hit go can help you refine your experiment, to be sure you are sensitive to the factors that might affect legitimacy and public trust.

Discussing your findings with affected stakeholders, and bringing them into the conversation and even decision making loop about whether to advance from pilot to production, can help make sure you are mitigating the risks, and maximising the benefits of a particular AI use.

Coda: Enabling collective veto and opt-out

Ideally - if you can, I would encourage you, in this kind of participatory pilot approach, to give community stakeholders an effective veto on the project going forward.

Too often projects rely on individual opt-out, but if the concerns of engaged members of a affected community can’t be overcome, this should be a signal that an application or use of AI is not yet ready to deploy.

Creating this powerful role for communities can also be an asset when negotiating with technology providers. It’s always helpful to be able to tell a tech account manager that it’s not only you they need to convince of a new tool, but that you’re consulting your communities too.

Deliberative review

So far - I’ve focussed on individual AI design and adoption decisions - but I also want to very briefly share an approach that’s capable of engaging with bigger policy questions, and engaging affected communities in setting broader principles for an organisational approach to AI.

This is the idea of a deliberative review.

Our work on this builds on the experience of the People’s Panel on AI - a deliberative citizens review of the AI Safety Summit and Fringe last November, with a representative group of 11 citizens from across England.

Over four days in London, those 11 citizens attended panel sessions to hear from AI experts, took part in hands-on workshops, and talked one-to-one about their hopes and fears for AI with scientists.

At the end of the process after deliberating on all the evidence they heard, they produced seven recommendations, which were received by an audience of industry, government and civil society.

There’s a lot more on the Connected by Data website about the People’s Panel, including a three minute video that I’d encourage you to take a look at.

However, I want to highlight a couple of specific design and learning points of note:

- Firstly, a review is about informing the debate, rather than making decisions. Unlike a Citizen’s Jury that might be charged with making a set decision, and citizens review can generate evidence and reports both for public consumption, and to be considered by decision makers alongside the other papers they look at. However, by having public perspectives in the papers and on the record, citizen reviews can support greater accountability about technology policy and decision making.

- Secondly, the review approach we took with the people’s panel leveraged existing events and activities: bringing citizens into the room to learn alongside everyone else - rather than having to organise lots of extra evidence sessions for our public participants. This made things cheaper and more efficient to run: helping us work ‘at the speed of AI policy making’.

- Thirdly, we created lots of opportunities for observers to watch the People’s Panel at work: increasing confidence in their findings, and helping re-assure decision makers that the public are able to take well-informed positions on the complex topics around AI.

As as I mentioned when discussing the governance stack, many of the citizens we brought together for the People’s Panel have gone on to continue their own pathways of participation around AI, taking the knowledge and confidence they have developed to join further AI debates, from local conversations about AI in education, to meetings with tech industry leaders or AI academics.

Recap

So - just to recap.

- There might feel like a lot of reasons to avoid engaging communities around AI: from the time and resource it might take, to feeling uncertain about how to do it effectively. But skipping engagement is a false economy. As machine-learning and AI replace legible algorithms of the state, participatory engagement is more important than ever.

- Long-term, aim for a governance stack that can robustly build in the voice of affected communities.

- Short-term, explore how to bootstrap engagement through participatory pilots, or deliberative reviews.

- There’s a growing community out there from which to draw support.

Here, and to share after, are some links to resources that have more on the themes I’ve discussed.