Phewy, I don’t know whether it’s the searing hot weather in the UK or a pretty full-on week but I’m wiped out.

It’s been super interesting, and we’ve made some good progress, but I admit I’m frustrated by my lack of progress on the proper writing tasks that I’m supposed to be working on. What happens is that I think “I’ll get this <small admin task> out of the way, and then get on with writing” and of course it turns out those small admin tasks just build up into occupying my week, or leave me tired out and unable to concentrate enough for anything creative. Next week I think I’ll try saving up the admin tasks to the end of the week instead of the big writing tasks!

That said, I did manage to write up everything from RightsCon and it looks as though other people have found that useful, so perhaps I shouldn’t berate myself too much!

Social innovation

The Bennett Institute for Public Policy held another Brown Bag lunch this week, this time with Halima Khan, talking about people-powered public services. Most of her talk focused on the idea of Social Innovation, particularly as defined by Geoff Mulgan in his book of the same name.

The main thrust of social innovation seems to be that if you empower communities to solve problems in partnership with the state, they’ll often come up with approaches that are more effective. This covers similar, parallel ground to our focus on collective data governance (including concepts such as co-production), and I think it’s interesting to explore how collective data governance might learn from, align with or arise as part of social innovation approaches.

Alima also recommended three other books:

- Radical Help: How We Can Remake the Relationships Between Us and Revolutionise the Welfare State by Hilary Cottam

- New Power: How it’s changing the 21st century and why you need to know by Henry Timms & Jeremy Heimans

- Rekindling Democracy: A Professional’s Guide to Working in Citizen Space by Cormac Russell

I have too much on my reading list, but I do have a couple of weeks holiday coming up in July so perhaps that will be a good opportunity to read them!

How much public awareness do we need for public participation?

In part because Tim couldn’t make it, I attended a webinar on “Perspectives on how to maximize public awareness for participatory data governance in African countries”, which was in part put on to discuss this report of the same name.

As well as the author of the report, Tọmíwá Ìlọrí from the Centre for Human Rights in South Africa, running through the report, there were also presentations from Hlengiwe Shelembe and Nomzamo Zondi from the Information Regulator in South Africa, and from Joel Abdulai Kallum from Chozen Generation in Sierra Leone. (There were a couple of other presentations but these were the ones that were most thought-provoking for me.)

Having been to several conversations about data protection in Africa over the past few weeks and months, the main thesis around data rights seems to be that they are lacking because there’s no public pressure to have them, which is due to lack of public awareness, and furthermore in countries that do have data rights in law, they are ineffective because no one uses them, which is due to lack of public awareness. The remedy is therefore raising awareness of both data harms (including mis-information) and data rights.

“Public participation” in these contexts is therefore discussed more in terms of exercising data rights than it is in terms of collective data governance. And I do think it’s right to see giving (or not giving) consent, and making complaints about the use of data, as a form of public participation. But it is typically a very individualised one, and one that atomises citizen power. If it’s the only kind of public participation you’re relying on, I believe it embeds existing power rather than challenging it.

To me, collective forms of governance are much more effective, and they’re most effective and legitimate when they include the public. My current taxonomy of these are collective and participatory ways of:

- creating principles, policies, processes and other “guardrails” around data governance

- making day-to-day operational decisions about data, such as whether to share it with a particular organisation

- providing accountability and redress for harms and impacts

People exercising their data rights falls into this third category. Collective and participatory ways of gaining accountability and redress tend to involve organisations (such as unions, advocacy groups, or even regulators) acting on behalf of people and communities. This is more effective than individualised approaches because groups and organisations are more powerful, but they’re also more likely to be able to have the resources and know-how to properly monitor and detect when harms occur.

Back to the webinar and the thesis that the way to address people not exercising their data rights is to educate them (which was the main thrust of the presentation from the SA Information Regulator). In my opinion, this is almost completely wrong-headed. Education might, just might, be something that could be effective in the long term, but there are lots of reasons that people don’t exercise their data rights aside from knowledge, and it certainly won’t be effective quickly. We’ve had information laws for decades in the UK and Europe, and we still don’t get many people effectively exercising their data rights.

So in my opinion it would be far far better to focus on more structural interventions and less on education. Better to bolster focused advocacy groups, for example, or require organisations to engage directly with the public around data governance, and include some education as part of the process.

These thoughts left me quite frustrated. But then the talk from Chozen Generation about the recent Sierra Leone census was fascinating and perked me up. You can read more about it in this article, but to summarise, the results of the census are unbelievable (showing huge falls in population in some areas and huge increases in others) and appear biased to favour the current ruling party.

This is a stark example both of the importance of the independence of national statistics offices, or indeed any data collection (and that independence is not a given); the importance of (actual and perceived) legitimacy of both data and the process of collecting it; and the potential and problems of community focused approaches to data collection. In many of the undercounted (opposition) areas in Sierra Leone, people say they were never visited by an enumerator. We might assume in other areas the enumerator may have invented people to include. Even when the national statistics office isn’t corrupt, enumerators need to be trusted both by the communities they have responsibility for, and by the NSO to whom they are reporting.

More generally it illustrates how intermediary organisations and people – enumerators in this case but in other cases data trustees or data union representatives – have a special, professional, role, not simply beholden to the interests of the communities they represent (which might benefit from being misrepresented) but also wider society.

Choosing sectors

One of the big things we managed to progress this week was identifying three sectors that we intend to proactively focus on over the next six months. (Subject to a little bit of deeper due diligence that we’re doing over the next few weeks). Those are education, debt, and housing.

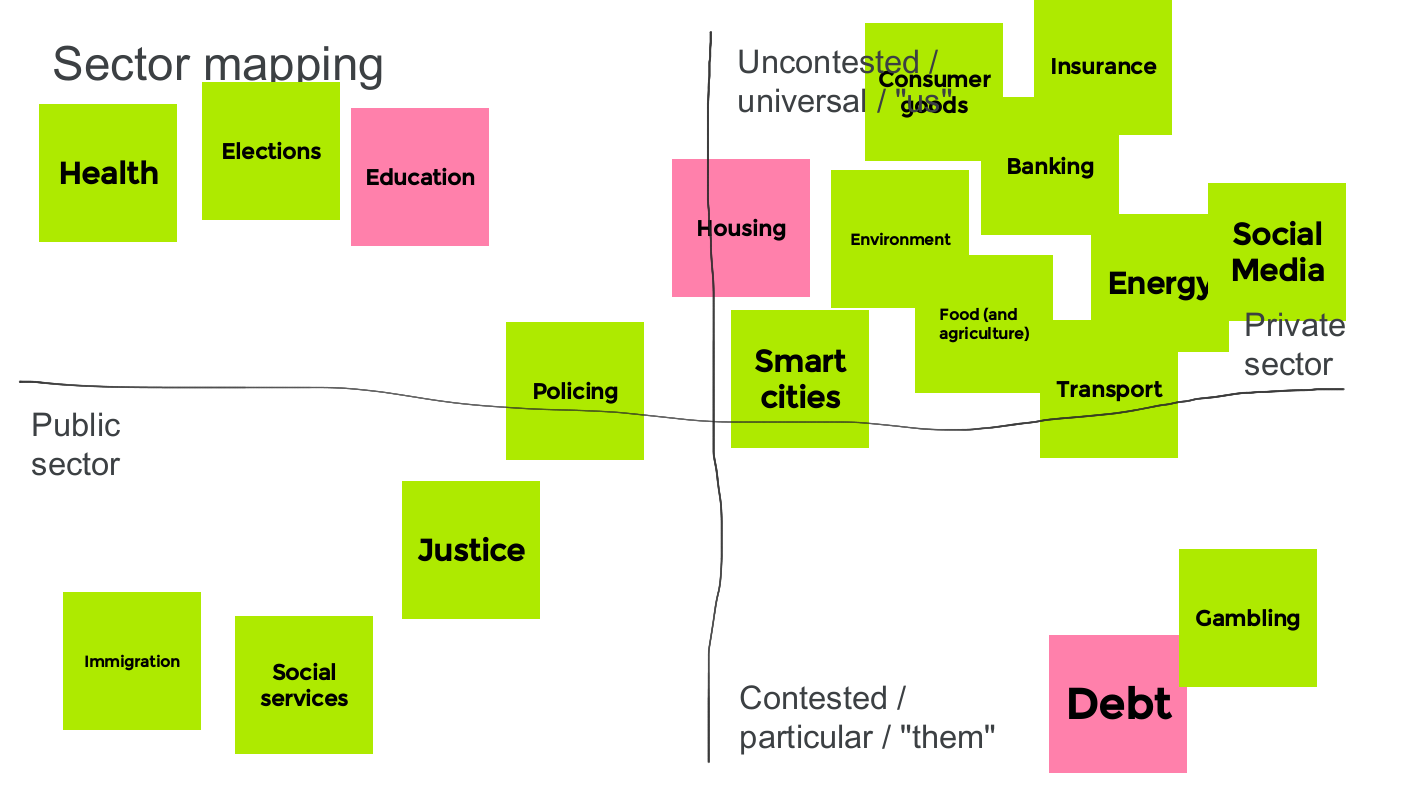

I wrote last week about some of the criteria for these sectors. Tim’s excellent amendment to the process was to map the long list of sectors against two dimensions, to ensure we selected not only sectors that met the set of criteria I discussed last week but had a range of characteristics. This will help us to explore and learn more about the kinds of messaging and stories that resonate in different contexts.

We were a bit stuck on what those dimensions should be, however. So I dug into my old knowledge elicitation toolbox and suggested using a card sort approach. Individually, we clustered the longlist of sectors into different groups, then named the dimension those groups represented, then shuffled the sectors and did it again to generate another dimension. In the end we created about a dozen, but with a certain amount of overlap between them.

The dimensions we ended up using were:

- **Universal/uncontested/”us” vs Particular/contested/”them”: **whether the sector is something we all interact with in some way (such as health) or something that some people (usually privileged people) might feel doesn’t affect them (such as gambling).

- **Public vs private service provision: **whether services in the sector are mostly provided by the public sector or the private sector.

Mapping sectors against a two-by-two matrix, we then tried to pick three sectors from different quadrants. We chose debt as the particular/private sector, housing as the universal/mixed sector, and education as the universal/public sector.

We also discussed how we would use two sectors that gain a lot of attention already: health and social media. We think health is ahead in collective data governance and a good source of examples to learn from. And we think we can touch on social media in more specific ways using the three sectors we’ve chosen as examples – for example exploring the use of targeted advertising for pay day loans, or training courses.

As I said, the next stage is to perform a bit of due diligence: exploring the actual issues and how we think collective data governance might help, and seeing if there are partners and upcoming opportunities for stories to land. If you’re working around any of these three areas – education, housing or debt – and would like to collaborate, do get in touch!

Exploring finance

The surprise engagement of the week was attending a session at Social Responsibility of Algorithms 2022, after Ellen asked some of her UK-based pals to attend a workshop aht was going on late on Friday evening, Australia time. The session turned out to be about finance, and therefore very relevant to our newly identified “Debt” sector.

The most useful part of this from my point of view was a presentation from the Commonwealth Bank describing some of the issues they see people experiencing. Of their six million customers, half are “just coping” and one in five are in financial trouble, living paycheck to paycheck and using products like payday loans.

The three challenges they observe are:

- under-saving for emergencies, with a third unable to survive a financial shock such as a loss of a job

- poor credit management, with 2m Australians struggling with high-cost debt, in persistent debt, or having balances on very high interest credit cards

- poor retirement outcomes, with people not set up well for their future needs

The speaker emphasised taking a behavioural lens and that people “fall to the level of systems and habits” (referencing Atomic Habits: Tiny Changes, Remarkable Results by James Clear). Factors include:

- New technologies making spending much more frictionless, with targeted advertising not helping, making it easier to unconsciously spend your future selve’s money

- Financial products that aren’t built for the present world, and that don’t provide feedback loops that are rapid enough (monthly credit card statements might be an example)

- The proliferation of financial products which obfuscates choices, alongside a reduction in the accessibility of good financial advice

- An increase in fraud and financial exploitation

- An increase in the use of algorithms to determine things like credit risk, and the fact these are biased against some groups

- The rise in the casualisation of work, including the gig economy and zero-hours contracts, which means more people have volatile and unpredictable paychecks; only one in two people on insecure incomes have enough financial buffer to cope

- The fact we are living longer, which means we need more careful planning to make our finances work until the end of our lives

In the workshop, we focused on four factors of financial wellbeing that had been identified, and that seem like some helpful categories to think about the impacts of debt:

- **meeting financial obligations: **being able to meet essential costs, e.g. the basic costs of living such as food, accommodation, or heat

- **financial freedom to enjoy life: **being financially able to choose to do things that you enjoy, such as entertainment or holidays

- **control of finances: **having the autonomy, awareness, and ability to make informed decisions about your finances

- **financial security: **knowing you can manage financially into the future, including in unexpected circumstances

We had some good discussion into which I surfaced both with my inner ranting about the limitations of “education” as a way of fixing problems like these, and the idea of social innovation and peer support (such as through credit unions) as an approach.

Other things this week:

- A really interesting discussion on the case database that Tim has been building, and where to take it next

- My one speaking engagement: a Practical GeoAI Ethics workshop held by Ordnance Survey / Geovation exploring how to embed ethics into work involving geospatial data. I’ve written that up separately but (as you’ll see if you read it) I found the presentation by PLACE particularly thought provoking and challenging.

- A great chat about potential approaches to gender data cooperatives with Bapu Vaitla from Data2X

- The GPSDD board meeting, where I was pleased to find other people similarly interested in the role of communities in data governance

- The ILPC board meeting – do submit papers for their annual conference!

- Oh yes, and the government published their response to last year’s “Data: a new direction” consultation! See my Twitter thread for a reaction…