Giving communities a powerful say in public sector data and AI projects

Communities are affected daily in both positive and negative ways by data governance decisions made by local and national governments. These arise through interactions with public services such as health and care; schooling; policing and justice; tax and benefits, as well as in more pervasive ways through government’s collection and dissemination of data, statistics and evidence to inform policymaking.

Over the past year (2024-25) we have been working to develop good practices and policies around public and community engagement with data and AI projects in the public sector. This work has been well-received, including partnerships with DSIT’s National Data Library team, the Office for Statistics Regulation, and TUC Cymru / the Welsh Government, and the development of a public-sector-wide community of practice on public participation.

The change of Government increases the opportunities for this work. The new Government is more open to working with civil society, and to participatory approaches. However, the public sector needs reskilling in how to meaningfully involve affected communities in decision-making. Developing robust norms, policies, guidance and experience of public engagement, particularly around data, digital, and AI, are necessary to ensure that the new Government’s pro-technology political stance translates into public and public sector adoption, and public good.

Our approach

We are grateful to The Mohn Westlake Foundation for granting us further funding to continue this work and specifically to:

- Continue supporting the dissemination, piloting and revision of guidance developed during the first year of this work, on public participation in the procurement of data and AI systems, the development of official statistics, and the sharing of data through the National Data Library.

- Run another two Design Labs, one in partnership with DSIT as the “digital centre” for government, to strengthen public engagement around the next stage of the digital transformation of the public sector, and one with a department such as DfE, DHSC, MoJ or MHCLG, to develop public engagement around AI tools being adopted in their sectors (education, health, justice or local communities).

- Continue and expand the Community of Practice for public participation practitioners in the public sector, including monthly meetings and another unconference to help them learn from each other and external experts.

- Support our ad-hoc engagement with policymakers and practitioners on the topic of public and worker engagement around data and AI systems in the public sector, including through events, meetings, advisory boards, consultation responses, case studies, blogs and commentary.

If we are successful, we will have embedded new participatory practices within dozens of public sector bodies, as the guidance we co-create is adopted by data and AI commissioners, statistics producers, digital service designers, and organisations sharing data through the National Data Library. We will also have developed a self-organising, engaged community of practitioners within the public sector who are able to engage with the public in meaningful ways.

Longer term, we will have increased the degree to which the public is engaged in the development and deployment of data and AI systems by the public sector. Through that, we will have reduced the degree to which these systems harm people, groups and communities, increased and improved the use of data to deliver public benefits, and built greater public trust and confidence in the use of data and AI across government.

Resources

Whenever we speak to public servants who are keen to involve the public more on decisions about data and AI, an early subject to be raised is always: who’s already done it, and how did they do it? People are understandably keen to learn from what has already been tried.

This blog/case study is part of a series exploring how public sector organisations involve the public, workers and civil society in decisions about data and AI, and some of the consequences when they do not. Read more about our work on public involvement in public sector data and AI.

The Department for Education (DfE) maintains records about everybody who has received state-funded education in England since 1996 in the National Pupil Database. It routinely shares this information with third parties. Civil society scrutiny unearthed failures in DfE’s data practices leading to a highly critical ICO audit in 2020, and a reprimand in 2022 for a data breach that led to education data being used by betting firms to verify the age of online gamblers.

This case study is part of a series exploring how public sector organisations involve the public, workers and civil society in decisions about data and AI, and some of the consequences when they do not. Read more about our work on public involvement in public sector data and AI.

One of the subjects we’ve been looking at as part of our project on giving communities a powerful say in public sector data and AI projects is statistics. In February, we ran a Design Lab with the Office for Statistics Regulation (OSR) on the role of public participation in statistics, as they refresh the Code of Practice for Statistics.

This blog/case study is part of a series exploring how public sector organisations involve the public, workers and civil society in decisions about data and AI, and some of the consequences when they do not. Read more about our work on public involvement in public sector data and AI.

The most recent Census 2021 found that there are 5.8 million unpaid carers in the UK, with 1.7 million people providing 50 or more hours of unpaid care per week. There are concerns that the official statistics do not reflect this, with implications for social policy and welfare design. In particular, how the ONS Labour Force quarterly figures define care as primarily ‘looking after the family and home’, and how welfare benefit policies mean many have to choose between working or receiving support. Care Full is a carer-led organisation to explore how we centre care in the economy. A key feature of that is to engage carers in the decisions about the collection and uses of data so that data reflects the experience of carers and can inform effective policy.

This case study is part of a series exploring how public sector organisations involve the public, workers and civil society in decisions about data and AI, and some of the consequences when they do not. Read more about our work on public involvement in public sector data and AI.

The London Borough of Camden has used public participation to help inform procurement as part of its mission-led approach to governing. This sits alongside its major public participation initiative around data, the Camden Data Charter. While requiring some investment and cultural changes, decisions made in these ways are seen as reflecting the priorities of the public; being authentic and evidence-led, which can help bring long-term political stability. They are also seen as improving community relations and increasing democratic engagement.

This case study is part of a series exploring how public sector organisations involve the public, workers and civil society in decisions about data and AI, and some of the consequences when they do not. Read more about our work on public involvement in public sector data and AI.

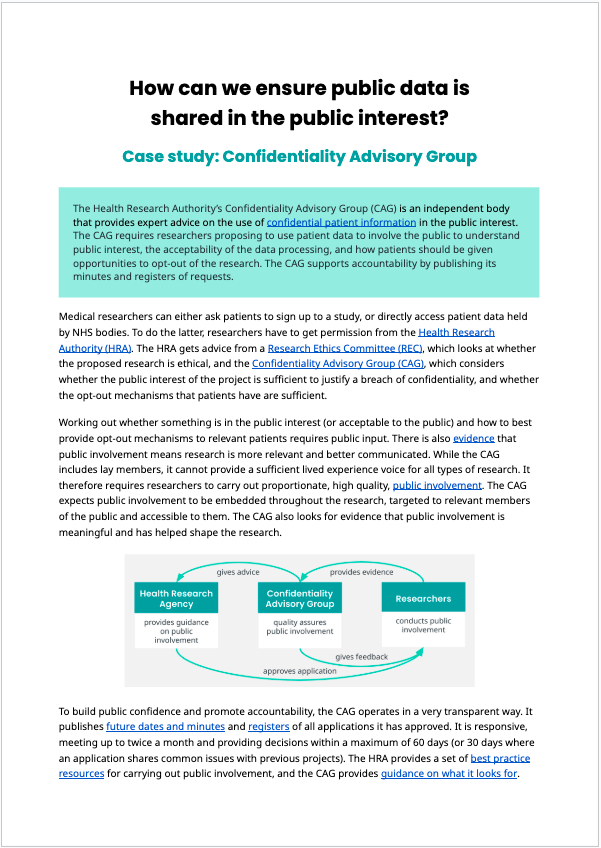

The Health Research Authority’s Confidentiality Advisory Group (CAG) is an independent body that provides expert advice on the use of confidential patient information in the public interest. The CAG requires researchers proposing to use patient data to involve the public to understand public interest, the acceptability of the data processing, and how patients should be given opportunities to opt-out of the research. The CAG supports accountability by publishing its minutes and registers of requests.

This case study is part of a series exploring how public sector organisations involve the public, workers and civil society in decisions about data and AI, and some of the consequences when they do not. Read more about our work on public involvement in public sector data and AI.

The Legal Aid Agency processes fee claims from legal professionals for their work on legal aid cases. In 2016 a new system was introduced as part of a wider digitisation programme, including the automation of assessing and awarding payment claims made by barristers. Case workers weren’t consulted on the introduction and functionality of the system, and there with weak mechanisms to feed back on its operation and impacts on workers and other stakeholders. Among wider significant disruption, it became apparent that the system had been incorrectly assessing claims, with an 19% error rate (compared to 3% for case workers) leading to costly overpayments, audits, corrections and revisions, as well as additional staff workload, disruption and dissatisfaction.

This case study is part of a series exploring how public sector organisations involve the public, workers and civil society in decisions about data and AI, and some of the consequences when they do not. Read more about our work on public involvement in public sector data and AI.

Events

On Wednesday 11 March 2026 at 2pm we will hold the final meeting of a community of practice as part of our project on Giving communities a powerful say in public sector data and AI projects.

This conference is for anyone interested in how to achieve better outcomes in the delivery of digital, data and AI work in the public sector through the involvement of the public, communities and workers. Come if you’re a public servant trying to engage or involve the public in your work on technology. Come if you’re working in civil society, in the union movement, or with grassroots groups, trying to be heard. Come to share what you’re up to, and to learn from others; leave with new insights, ideas, and connections.

On Wednesday 11 February 2026 at 2pm we will hold the sixteenth meeting of a community of practice as part of our project on Giving communities a powerful say in public sector data and AI projects.

On Wednesday 14 January 2026 at 2pm we held the fifteenth meeting of a community of practice as part of our project on Giving communities a powerful say in public sector data and AI projects.

On Wednesday 10 December 2025 at 2pm we held the fourteenth meeting of a community of practice as part of our project on Giving communities a powerful say in public sector data and AI projects.

On Wednesday 19 November 2025 at 2pm we held the thirteenth meeting of a community of practice as part of our project on Giving communities a powerful say in public sector data and AI projects.

On Wednesday 8 October 2025 we held the twelfth meeting of a community of practice as part of our project on Giving communities a powerful say in public sector data and AI projects.

On Wednesday 10 September 2025 at 2pm we held the eleventh meeting of a community of practice as part of our project on Giving communities a powerful say in public sector data and AI projects.

Jeni is attending a workshop on ‘AI in policing’ hosted by JUSTICE, in London.

Tim attended the presentation of the “Our Schoolwork, Our Say” Legislative Theatre performance with young people sharing ideas around the governance of education data.

How can schools consult with parents, pupils and teachers on school-level policies on AI in ways that help them to advance their rights, learn to think critically about technology and its capability so that they adopt it in ways that are beneficial, and exercise their democratic muscles?

On Wednesday 9 July 2025 at 2pm we will hold the tenth meeting of a community of practice as part of our project on Giving communities a powerful say in public sector data and AI projects.

The Blueprint for Modern Digital Government commits to providing “clear and actionable guidance to embed best practices in trust and responsibility” and cites Camden Council’s data charter, co-created with citizens, as an example of how public bodies can maintain public trust and confidence. It says that civil society groups will be “invited to co-design services in partnership with communities and public sector workers to ensure they are responsive to their needs.”

As governments increasingly use AI to deliver public services, key decisions—especially around procurement—often happen behind closed doors, without input from the communities most affected.

Local government is at the front-line in piloting and deploying new AI and data-driven tools in the search for savings and service improvement. How can and should local governments engage with local residents when planning, evaluating and governing data and AI-enabled reforms? And what are the challenges and opportunities of involving the public in decision-making on data and AI uses?

On Wednesday 18 June 2025 at 2pm we held the ninth meeting of a community of practice as part of our project on Giving communities a powerful say in public sector data and AI projects.

On 12 June Jeni Tennison, our Founder and Executive Director, will be the keynote at the UK Census User Conference. She will speak on the importance of user and public voice in official statistics.

Is the law keeping pace with technology to protect people’s rights and uphold transparency and accountability standards? How can public, regulatory and human rights law help ensure technologies are deployed for the benefit of society? The Public Law and Technology Conference seeks to consider these questions.

Tim Davies, Anna Beckett and members of the Public Voices in AI People’s Advisory Panel, spoke at the ESRC Digital Good Network’s webinar series with the Public Voices in AI project about how public voices can be put front and centre in artificial intelligence research, development and policy.

In May 2025 National Voices and Connected by Data hosted a 90 minute roundtable under the heading ‘aligning AI innovation in healthcare with patient need and the future NHS’.

On 19 May Jeni Tennison, our Founder and Executive Director, will be the keynote at UK Evaluation Society’s ‘Evaluation Conference’ 2025’ event.

She will be speaking on “Involving communities in evaluating public sector AI”.

On Wednesday 14 May 2025 at 2pm we will hold the eight meeting of a community of practice as part of our project on Giving communities a powerful say in public sector data and AI projects.

In contrast to the halting approach to reform from the current UK government, Donald Trump and Elon Musk have moved fast to slash staff and programmes. That has led some of those frustrated with the slow pace of government reform in the UK and elsewhere to see DOGE as a model for radical reformers.

On Wednesday 9 April 2025 at 2pm we will hold the seventh meeting of a community of practice as part of our project on Giving communities a powerful say in public sector data and AI projects.

Do With is not a new organisation or formal campaign. Instead, it hopes to be a grassroots movement for change led by the people who are part of it. As such, this event on 26 March will be a space for attendees to share ideas on how they would like to deliver change and to connect people together who want to work on specific ideas. Those ideas could operate within public sector teams and organisations or within communities or both; and could operate at local, regional or national level.

Unconferences are participant-driven meetups that focus on sharing, learning and community building.

This unconference was for people (particularly inside the public sector) who are interested in ensuring that public, community and worker voices are heard in decisions about data, digital and AI.

On Wednesday 12 March 2025 at 2pm we will hold the sixth meeting of a community of practice as part of our project on Giving communities a powerful say in public sector data and AI projects.

The Procurement Act is about much more than new legislation – it’s an opportunity to re-imagine how buyers and suppliers can work together to deliver outstanding public services. The biggest set of regulatory changes in a generation will create new opportunities – but also challenges as the entire supply chain adjusts to this new landscape.

On 25 February Jeni Tennison, our Founder and Executive Director, will be the keynote at TPXimpact’s ‘Power of Data’ event in London, Convening the UK’s top data leaders and policymakers to shape the future of government data strategy.

On Wednesday 12 February 2025 at 2pm we will hold the fifth meeting of a community of practice as part of our project on Giving communities a powerful say in public sector data and AI projects.

The Office for Statistics Regulation (OSR) is currently running a consultation on a refresh of the Code of Practice for Statistics (the Code) to ensure it continues to meet the needs of its wide and evolving audience. The Code sets the standards that producers of official statistics should commit to. Compliance with the Code gives people confidence that published government statistics have public value, are high quality, and are produced by people and organisations that are trustworthy.

On Wednesday 15 January 2025 we held the fourth meeting of a community of practice as part of our project on Giving communities a powerful say in public sector data and AI projects.

On Wednesday 11 December 2024 at 2pm we will hold the third meeting of a community of practice – an online workshop – as part of our project on Giving communities a powerful say in public sector data and AI projects.

The Labour Government has a manifesto commitment to build a National Data Library (NDL) “to bring together existing research programmes and help deliver data-driven public services, whilst maintaining strong safeguards and ensuring all of the public benefit”. This commitment is in the context of a drive for greater AI innovation and adoption across the economy.

Digitalisation within the public sector continues at pace. UK Labour is strongly signalling a technology-driven strategy for wide ranging public services reform and a significant role for private sector vendors.

In order to shape public sector digitalisation towards fair and equitable outcomes for workers and communities alike, a range of voices and perspectives need to be meaningfully incorporated at all stages.

On Thursday 3 October 2024 we held the second meeting of a community of practice as part of our project on Giving communities a powerful say in public sector data and AI projects.

On Thursday 18 July 2024, on Zoom, we held the first meeting of a community of practice as part of our project on Giving communities a powerful say in public sector data and AI projects.

With the use of AI and data driven tools increasing in the civil service and by public servants, Adam spoke on a panel at the annual conference of the FDA, the union representing public service managers and professionals.

Appearing alongside a colleague from the TUC and in conversation with the FDA’s General Secretary, Adam discussed Connected by Data’s work with TUC Cymru and the implications of the Data Protection and Digital Information Bill for public service workers.

Opinion

A strategic approach to the adoption of AI in the public sector should focus investments in places that will make a difference. Saving money is one of the big priorities for this government, so where should it target AI to realise those ambitions?

I’ve been appointed to an external advisory panel to support the design of the “digital centre” in DSIT (currently a smooched together combination of GDS, CDDO and i.AI). I put out a call on Bluesky for reckons and pointers that has had quite the response, summarised here by Tim Paul but you should go read all the responses. I want to try here to distil some of the topics, questions and opinions around the design of public services, technology support, and what DSIT needs to do as the “digital centre”.

The Department for Education has recently released public attitudes research on what parents and pupils think about AI in education, as part of its announcement of a £4m investment to create a dataset to support building AI tools. This is a bit of a hangover from the previous government (the work was carried out earlier in 2024), but reflective of the current government’s commitment to maximising adoption of AI across the public sector.

Before I dig into the details, I should first say that it’s fantastic to see public sector organisations carrying out public attitudes research to inform how they approach the adoption of AI. This kind of research can be used to prioritise investments, inform governance processes to address anticipated harms, and identify barriers and blockers to adoption, as well as working out how to communicate about governmental plans.

Here I want to pull out some specific insights from the research that highlight considerations for how technology is rolled out for public services, namely about profit sharing; schools as trusted decision makers; and points about equity and choice. Then I’m going to discuss some lessons that should be taken into future similar public engagement exercises, particularly about shifting understanding and acceptance of technology; consulting teachers and workers; and the overall approach we need of “you said, we listened”.

I posted recently about the challenge of adoption of AI by the public sector.

There are two sides to this: how the public sector adopts AI itself, and how the public adopts AI-driven public services.

I’ve posted recently about the challenge of purpose and priorities in the adoption of AI by the public sector. This blog post expands on this to look not at what I think the priorities should be, but about how they should be decided, and that prioritisation method institutionalised given it’s not a one off exercise.

Weeknotes

Weeknotes are a combination of updates and personal reflection written on a routine basis